The Truth About Good Debt vs Bad Debt in 2026 (Most People Get This Completely Wrong)

Look, I’m just going to be straight with you from the start.

Most articles about good debt versus bad debt will give you the same tired textbook definitions. “Good debt builds wealth, bad debt drains it.” Cool. Thanks for nothing.

But here’s what they won’t tell you: I’ve seen people with “good debt” lose their homes. I’ve watched college graduates with “investment in themselves” student loans move back in with their parents at 30. And I’ve met business owners whose “strategic leverage” turned into bankruptcy.

Here’s the hard truth for 2026: For many middle-class families globally, the biggest financial threat isn’t bad debt. It’s too much “respectable” debt.

The mortgage you’re supposed to have. The student loans that were “investments.” The car payment that’s “normal.” Stack enough good debt together, and you’re broke with a good credit score.

I’ve personally watched smart, high-income people drown under this kind of debt. Doctors. Engineers. Business owners. It rarely starts with a bad decision. It starts with stacking too many “reasonable” ones.

So yeah, the whole good debt vs bad debt thing? It’s way more complicated than the finance bros on Twitter want you to believe.

Let me show you what’s really going on.

Table of Contents

- What Good Debt vs Bad Debt in 2026 Actually Means

- How Good Debt vs Bad Debt Looks Globally in 2026

- Examples of Good Debt in Personal Finance

- The Bad Debt Hall of Shame

- The Grey Zone Nobody Talks About

- How to Tell If Debt Is Good or Bad: My 4-Test Framework

- Can Debt Build Wealth? Myths About Good Debt vs Bad Debt in 2026

- How to Actually Manage Debt Without Losing Your Mind

- Your Questions Answered: Good Debt vs Bad Debt Examples

What Good Debt vs Bad Debt in 2026 Actually Means

Picture this scenario.

Sarah borrows $200,000 for medical school. Her friend Marcus swipes his credit card for $5,000 worth of limited edition sneakers. The interest rate? 22%.

Five years later, Sarah’s pulling in $180,000 as a physician. The student loans? She’s handling them fine.

Marcus? Still chipping away at that $5,000. Except now it’s $8,200 because of interest. And those sneakers? They’re in the back of his closet. He hasn’t worn them in three years.

This isn’t a morality tale. Sarah isn’t “better” than Marcus. But their debt decisions? Completely different outcomes.

Here’s the thing though—and this is important—Sarah’s loans could have easily gone the other direction. If she’d dropped out of med school in year two, that $200,000 would’ve been an absolute disaster. So even “good debt” isn’t automatically good.

The Real Definition (That Actually Helps You)

Good debt is money you borrow that has a realistic shot at increasing your net worth or income over time. Notice I said “realistic shot.” Not guaranteed. Not marketed to you as an investment. Actually probable based on real data.

Bad debt is borrowing for stuff that loses value or gives you nothing back except the joy of spending money you didn’t have.

Sounds simple, right?

It’s not.

Because 2026 has made this whole conversation infinitely more complicated.

Why Everything Changed (And Why It Matters to You)

We’re living through a completely different financial reality than our parents faced.

Interest rates? They’re still elevated after the Federal Reserve spent 2022-2023 aggressively hiking rates to kill inflation. Yeah, they’ve eased a bit. But we’re nowhere near the cheap money era of 2010-2021.

Credit card APRs are averaging 22.3% right now. That’s not a typo.

Student loan debt in the US hit $1.83 trillion. The average federal student loan borrower owes $39,547. And here’s the kicker—9.4% are in default. That’s not a rounding error. That’s nearly 1 in 10 people who borrowed for “good debt” education who can’t pay it back.

Then there’s Buy Now Pay Later.

This didn’t even exist a decade ago. Now it’s a $560.1 billion global market. And guess what the miss-payment rate is? Between 34-41% overall. For Gen Z specifically? 51% miss payments.

Let me say that again. More than half of young BNPL users are missing payments on debt that doesn’t even show up on their credit reports.

According to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, people are stacking multiple BNPL loans from different companies without even realizing how much they owe total. It’s invisible debt. Until it’s not.

Meanwhile, housing prices have gone absolutely insane globally. The “good debt” mortgage that was supposed to build wealth? In many markets, it’s just making people house-poor.

So when we talk about good debt vs bad debt in 2026, we’re not talking theory. We’re talking survival.

How Good Debt vs Bad Debt Looks Globally in 2026

This isn’t just an American problem. The debt conversation is playing out differently across the world, and understanding these patterns matters—especially if you’re considering international opportunities or just want perspective on your own situation.

United Kingdom: Mortgage Rate Shock

UK homeowners are experiencing what might be the most dramatic mortgage crisis in a generation. After years of rock-bottom rates (some mortgages below 1%), the Bank of England’s aggressive rate hikes sent borrowing costs soaring to 5-6% on average mortgages by late 2024.

Thousands of homeowners who locked in cheap 2-year fixed rates in 2021-2022 faced payment increases of £500-800 monthly when remortgaging in 2023-2024. That “good debt” mortgage became unaffordable overnight for many families.

Canada: Housing Affordability in Crisis

Canada’s housing market makes the US look affordable. According to the OECD’s household debt statistics, Canadian household debt-to-income ratio hit 181.7% in 2024—meaning the average household owes nearly twice their annual income.

Toronto and Vancouver home prices pushed average mortgages above $600,000-800,000. With the Bank of Canada raising rates aggressively, many Canadians are facing a painful choice: sell at a loss or struggle with payments consuming 40-50% of gross income.

Is a mortgage good debt in Canada right now? Depends heavily on your location and income stability.

India: Education Loan Explosion

India’s education loan market has grown dramatically as middle-class families invest in their children’s education—both domestically and abroad. The Reserve Bank of India reports education loans outstanding exceeded ₹95,000 crores (roughly $11.5 billion) in 2024.

Interest rates typically range from 7.5-12% depending on the institution and loan amount. For students studying abroad, the debt burden can exceed ₹20-40 lakhs ($25,000-50,000), which is enormous relative to typical Indian starting salaries.

The twist? Many Indian families treat education debt as sacred—it’s paid before almost anything else. Cultural attitudes toward debt repayment create different outcomes than Western markets.

Australia: HECS-HELP Makes Student Loans Different

Australia has one of the world’s most interesting student loan systems. The Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS-HELP) provides government loans with no interest—just indexation to inflation.

Repayment is income-contingent, starting only when you earn above a threshold (around $51,550 in 2025). If you never earn enough, you never repay. If you leave Australia permanently, the debt essentially disappears.

This makes Australian student debt fundamentally different from US or UK models. It’s closer to a graduate tax than traditional debt. The question “is student loan good debt” has a completely different answer in Sydney than San Francisco.

Europe: Stricter Lending, Different Dynamics

European mortgage lending is generally more conservative than Anglo-American markets. Many European countries require 20-30% down payments as standard. Mortgage terms are often shorter (15-20 years common). And strict debt-to-income rules prevent the overleveraging that contributed to the 2008 crisis.

Credit card debt is less prevalent. BNPL exists but hasn’t exploded to US levels. Consumer debt is generally lower relative to income.

The result? Europeans typically carry less household debt but also build home equity more slowly and have less access to credit for entrepreneurship or investment.

Different system, different trade-offs.

The Global Lesson

What qualifies as good debt or bad debt isn’t universal. It depends on:

- Local interest rate environment

- Cultural attitudes toward debt

- Lending regulations and protections

- Income levels and stability

- Housing market dynamics

- Social safety nets

But the fundamental principle holds everywhere: debt is only “good” if it genuinely improves your financial position over time without excessive risk. That’s harder to achieve than most people realize, regardless of country.

Quick Reality Check: Good Debt vs Bad Debt

| What We’re Comparing | Good Debt | Bad Debt |

|---|---|---|

| Interest Rate | Usually under 8% (but not always) | Often 15-22%+ |

| What You’re Buying | Something that should make you money | Something that makes you feel good temporarily |

| What Happens to It | Goes up in value or earns income | Loses value or gives you nothing |

| Tax Situation | Sometimes deductible | Almost never |

| Payment Stress Level | Manageable if you did the math right | Keeps you up at 3am |

| Examples | Mortgage, some student loans, business loans | Credit cards, payday loans, financing a vacation |

But don’t get comfortable with this table. Real life is messier. A lot messier.

Examples of Good Debt in Personal Finance (And When Borrowing Actually Makes Sense)

Let’s get real about the most common types of “good debt.”

Because calling something good debt doesn’t magically make it smart. Context is everything. Your situation is everything.

Is Your Mortgage Actually Good Debt?

The standard pitch:

“Homeownership builds wealth! Housing appreciates! You’re not throwing money away on rent!”

Okay, there’s some truth there. The Federal Housing Finance Agency shows US home prices have historically appreciated around 6% annually over long periods. If you borrow $300,000 and that house is worth $450,000 in 15 years while you’re building equity? That’s powerful.

Plus you get:

- Mortgage interest deduction (if you itemize)

- Fixed housing costs while rent keeps climbing

- Forced savings through equity

- A place to actually live

But here’s where it goes sideways:

Not everyone who took out a mortgage in 2007 built wealth. Some lost everything.

A mortgage stops being good debt when:

You’re stretching to afford it. If you’re spending over 30% of your gross income on housing, you’re one emergency away from trouble.

You’re banking on appreciation. “It’ll be worth more later” is speculation, not strategy.

You got a variable rate. And rates go up. And suddenly you can’t afford your house.

Your local market is tanking. Not every city goes up.

You’re treating home equity like a piggy bank. Taking out second mortgages for cars and vacations.

Real example from someone I know:

Jessica bought a $400,000 home in 2020. Put down 20%. Got a 3.5% fixed rate. Her payment is $1,600 monthly—less than she’d pay in rent for something comparable. Her home is now worth $480,000.

That’s good debt in action.

Her neighbor bought a $600,000 house the same year. Put down 3%. Got an adjustable rate because the initial payment was lower. Fast forward to now? His payment jumped from $2,800 to $3,600. And he owes more than the house is worth.

Same market. Same timing. Completely different outcomes.

Student Loans: The “Investment in Yourself” That Sometimes Isn’t

This is where things get controversial.

I’ll probably get hate for this, but whatever. Not all student loans are good debt. Some are financial disasters wrapped in academic robes.

I learned this the hard way watching friends graduate. One got a computer science degree with $35,000 in federal loans and walked into a $90,000 job. Another got a liberal arts degree with $95,000 in private loans and struggled to find work paying $40,000. Both believed they were making “investments in themselves.”

Only one was right.

The case that sounds good:

College graduates earn a median of $77,636 annually according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. High school graduates? $46,748. Over 40 years, that’s potentially $1.2 million more in earnings.

So borrowing $30,000 to unlock that? Seems worth it.

Federal student loans also give you:

- Fixed interest rates (6.53% for undergrad Direct Loans in 2024-25)

- Income-driven repayment if things get tough

- Possible loan forgiveness

- Interest deductions

The reality nobody wants to admit:

42.7 million Americans are carrying federal student loans. Total debt? $1.69 trillion. Delinquency rate? 9.4%.

If student loans were such obviously good debt, why are so many people struggling to pay them back?

Here’s when student loans become questionable at best:

Your total debt is more than your expected first-year salary. If you’re borrowing $100,000 to get a job that pays $45,000, the math doesn’t work.

You’re pursuing a degree with limited earning potential. I’m not being a snob. I’m being realistic. If your field doesn’t pay well, don’t bury yourself in debt for it.

You’re using private loans with rates above 8-10%. Federal loans have protections. Private loans? You’re on your own.

You haven’t actually researched job placement rates. Program marketing is not the same as reality.

You’re going to grad school because you don’t know what else to do. That’s not a plan.

Example:

A software engineer graduates with $40,000 in federal loans and immediately gets a job paying $85,000. That’s probably good debt. They can handle the payments and the degree opened the door.

An arts graduate with $120,000 in private loans at 9% interest and no clear career path? That’s a crisis waiting to happen. And before you get mad—I’m not saying arts degrees are worthless. I’m saying $120,000 in high-interest debt for them is dangerous.

Business Loans: Good Until They’re Devastating

Borrowing for business can be incredibly smart or catastrophically stupid. There’s not much middle ground.

When it works:

You have a proven business model. Not an idea. Not a dream. Actual customers paying for actual products or services.

The loan generates more revenue than it costs. If you borrow $50,000 at 8% and it helps you make an extra $100,000 in profit, you win.

You’re buying equipment or inventory that drives growth. Tangible investments with measurable returns.

You can handle the debt even if things slow down for a bit.

When it destroys people:

Borrowing to cover operating losses. If your business isn’t profitable without the loan, the loan won’t fix it.

No clear path to profitability. Hope isn’t a business plan.

Interest rates so high that profit becomes impossible.

Personally guaranteeing business debt you can’t afford. Then your personal life gets destroyed too.

Career Development Loans (The Underrated Option)

This doesn’t get talked about enough.

In 2026’s job market, skills matter more than credentials sometimes. And the right training can pay off fast.

What actually works:

Coding bootcamps with job guarantees or income-share agreements. You don’t pay unless you get hired.

Professional certifications that lead to clear salary bumps. CPA, PMP, certain tech certifications.

Trade schools for in-demand work. Electricians, plumbers, HVAC techs—these people make serious money.

The rule:

Cost should be less than one year’s salary increase. Completion rate should be over 70%. Job placement should be over 80%. The skill should be in actual demand, not just trendy.

The Bad Debt Hall of Shame

Okay, let’s talk about the debt that’s just straight-up bad.

No nuance here. These will mess up your financial life.

Credit Card Debt: The Interest Rate Monster

I need to be clear about something first.

Using credit cards isn’t automatically bad. If you charge $1,000, collect 2% cash back, and pay it off in full? That’s smart. You’re using other people’s money for free and getting rewarded for it.

The problem starts when you carry a balance.

The math is brutal:

Average credit card APR right now? 22.3%. That’s insane.

If you carry a $5,000 balance and only make minimum payments, you’ll pay over $7,700 in interest across 23 years. That $5,000 purchase actually costs you $12,700.

Americans collectively owe $1.23 trillion on credit cards right now. According to Federal Reserve data, that number keeps climbing. If even half of that is accruing interest at these rates, we’re talking hundreds of billions in pure interest payments going to banks instead of building wealth.

You’re in trouble when:

You’re making minimum payments while adding new charges. That’s a losing game.

You’re using cash advances. Those typically hit 24.5% APR plus fees immediately.

You’re doing balance transfers without fixing your spending. You’re just moving debt around.

You’re using cards for groceries because you ran out of money. That’s not a credit problem. That’s an income or spending problem that credit is making worse.

The one exception:

Strategic balance transfers to 0% APR cards can work. But only if you stop adding debt and have a realistic payoff plan. Otherwise you’re just delaying the inevitable.

Payday Loans: Legal Robbery

There’s no defending these.

Payday loans often have effective APRs over 300-400%. That’s not a typo. That’s predatory lending that somehow remains legal.

Here’s the typical trap:

You need $500 to fix your car. You take a payday loan with a $75 fee due in two weeks.

Payday comes. You can’t pay back $575. So you roll it over for another $75.

Six months later, you’ve paid $450 in fees on a $500 loan. And you still owe the $500.

If you’re even considering a payday loan, stop. Ask your employer for an advance. Find a community assistance program. Sell something. Literally almost anything is better than payday loans.

Is Buy Now Pay Later Bad Debt? The Stealth Crisis

This deserves its own section because it’s the newest threat and people don’t take it seriously enough.

BNPL sounded harmless at first. Split a $400 purchase into four $100 payments. No interest. Easy.

Here’s what’s actually happening.

The 2026 BNPL situation:

Global market hit $560.1 billion. That’s massive.

34-41% of users miss payments. Gen Z? 51% miss payments.

Most BNPL debt isn’t reported to credit bureaus. It’s phantom debt.

People have multiple BNPL loans from different companies without realizing total exposure.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau found that 63% of BNPL users had simultaneous loans at one firm. 33% had loans at different firms at the same time.

You can’t see the problem until it’s crushing you.

When BNPL becomes dangerous:

You’re using it for groceries. That’s a sign you can’t afford your life right now.

You’ve lost track of how many active BNPL loans you have.

You’re missing payments because you forgot or couldn’t pay.

You think of it as free money instead of real debt.

Financing Depreciating Assets: The Luxury Trap

Financing a vacation, designer clothes, or the latest iPhone creates debt without creating value.

Here’s why it’s terrible:

Finance a $60,000 luxury car at 6% for 72 months. Your payment is $987 monthly.

After three years, you’ve paid $35,532 total. Maybe $28,000 went to principal.

But the car is now worth $38,000. You barely built equity because depreciation ate your payments.

Compare that to financing a commercial vehicle for a business that generates $2,000 monthly profit. Same price. Completely different outcome.

Warning signs:

The loan term is longer than the item lasts.

Interest payments exceed the item’s depreciation.

You’re financing wants instead of needs.

The debt will outlast your enjoyment of the purchase.

The Grey Zone Nobody Talks About: When Good Debt Becomes Bad

Here’s what makes me crazy about most personal finance advice.

They act like good debt stays good and bad debt stays bad. Like the categories are fixed.

That’s not how life works.

Good debt can absolutely become bad debt. And it happens more often than people admit.

Too Much of a Good Thing: Overleveraging

Your first mortgage on a home you can comfortably afford? Probably good debt.

Second mortgage for a vacation property that stretches your budget? Getting questionable.

Adding a home equity line of credit to renovate? Now you might be overleveraged.

Warning signs:

Total debt payments exceed 40% of gross income. Multiple “good debt” categories without income growth. Using new debt to service existing debt—that’s the beginning of a spiral. Missing one paycheck would cause defaults. Constant money stress.

⚠️ CRITICAL WARNING: If your total debt payments exceed 40% of gross income, you are financially fragile—even if your credit score is excellent. One income disruption and everything collapses.

Case Study: The Doctor Who Wasn’t Rich

I know someone who makes $250,000 a year. Doctor. Should be financially set, right?

Here’s his debt:

- $300,000 in student loans

- $600,000 mortgage

- Two car payments totaling $1,200 monthly

- Business loan for private practice

Total monthly debt payments? $8,500. That’s 41% of gross income.

One slow month at the practice and everything wobbles. Despite the six-figure income, he’s financially fragile. All that “good debt” added up to something that’s not good at all.

Variable Rates in a Volatile World

What looked like good debt at 3% can become crushing at 7%.

This hits:

- Adjustable-rate mortgages

- Variable-rate student loans (private ones)

- Business lines of credit

- Some home equity lines

Between 2022-2023, the Federal Reserve raised rates faster than they had in decades. People with variable-rate debt got destroyed.

Example:

A $300,000 ARM mortgage starting at 2.5% had a payment of $1,185 monthly.

When it reset to 6.5%, the payment became $1,896.

That’s an extra $711 per month. Or $8,532 annually. Money that has to come from somewhere.

When Your Income Assumptions Were Wrong

This particularly hits student loans and business debt.

Student loan disaster:

You borrow $100,000 for a master’s degree. The program says graduates make $90,000 starting. Sounds worth it.

Reality? You can’t find a job for six months. When you do, it pays $55,000.

Your student loan payment is $1,100 monthly. Your take-home pay is $3,400.

That’s 32% of net income before you’ve paid for housing, food, or anything else.

The debt was supposed to be an investment. It became an anchor.

Business debt that doesn’t perform:

A restaurant owner borrows $200,000 at 8% to expand. The business plan projected $400,000 in additional annual revenue.

Instead, costs went up and customers came slower than expected. The expansion adds $100,000 in revenue but costs $90,000 to run.

Debt service is $24,000 annually on $10,000 in additional profit.

The math doesn’t work. The loan is strangling the business.

Life Happens: Income Instability

Good debt assumes stable income. When that changes:

Job loss or business downturn. Industry disruption. Health issues. Economic recession.

Example:

During COVID in 2020, millions of people with “good debt” suddenly had no income. The debt didn’t change. Their ability to pay it did.

Student loans. Mortgages. Business loans. Car payments. All still due. But the paycheck stopped.

The lesson:

Good debt requires income stability or massive emergency reserves. Without that foundation, even optimal debt becomes dangerous.

Lifestyle Inflation: Earning More, Owing More

This is the most insidious pattern.

You graduate with $40,000 in student loans. You get a good job. Instead of crushing that debt, you:

Get a car loan. Upgrade your apartment. Start using credit cards more. Buy more stuff.

Five years later you’re earning more but owing more. The “good debt” is still there, joined by consumption debt. Your net worth is actually lower than when you started.

The psychology is simple. Rising income feels like permission to increase borrowing.

But debt growing faster than income is the path to permanent struggle.

How to Tell If Debt Is Good or Bad: My 4-Test Framework

Most people evaluate debt emotionally.

“Can I afford the payment?”

That’s not enough. That’s barely even a starting point.

You need a system. Here’s mine.

Test #1: The ROI Test

The question: Will this debt generate a financial return that exceeds its cost?

Not maybe. Not hopefully. Realistically, with actual data.

How to calculate:

- Add up total cost (principal + all interest over the loan’s life)

- Estimate total financial benefit (increased income, asset appreciation, business revenue)

- Calculate the difference

Pass threshold: Benefit should exceed cost by at least 2:1. You need a safety margin for when things don’t go perfectly.

Example 1:

Borrowing $50,000 for a coding bootcamp at 7% interest over 5 years.

Total cost: $59,410 (principal + interest)

Expected salary increase: $35,000 annually

Over 5 years: $175,000 additional earnings

ROI ratio: 2.95:1 → PASS

Example 2:

Borrowing $30,000 for a master’s degree in a saturated field.

Total cost: $38,500 over 10 years

Expected salary increase: $8,000 annually

Over 10 years: $80,000 additional earnings

ROI ratio: 2.08:1 → Technically passes but barely. I’d look for alternatives.

Example 3:

Financing a $40,000 boat at 9% for 10 years.

Total cost: $60,666

Financial return: $0

ROI ratio: Doesn’t apply → FAIL. This is pure consumption.

Test #2: The Cash Flow Test

The question: Can you actually afford the payments within a healthy budget?

Not “can I technically make the minimum payment if I sacrifice everything else.” Can you pay this comfortably?

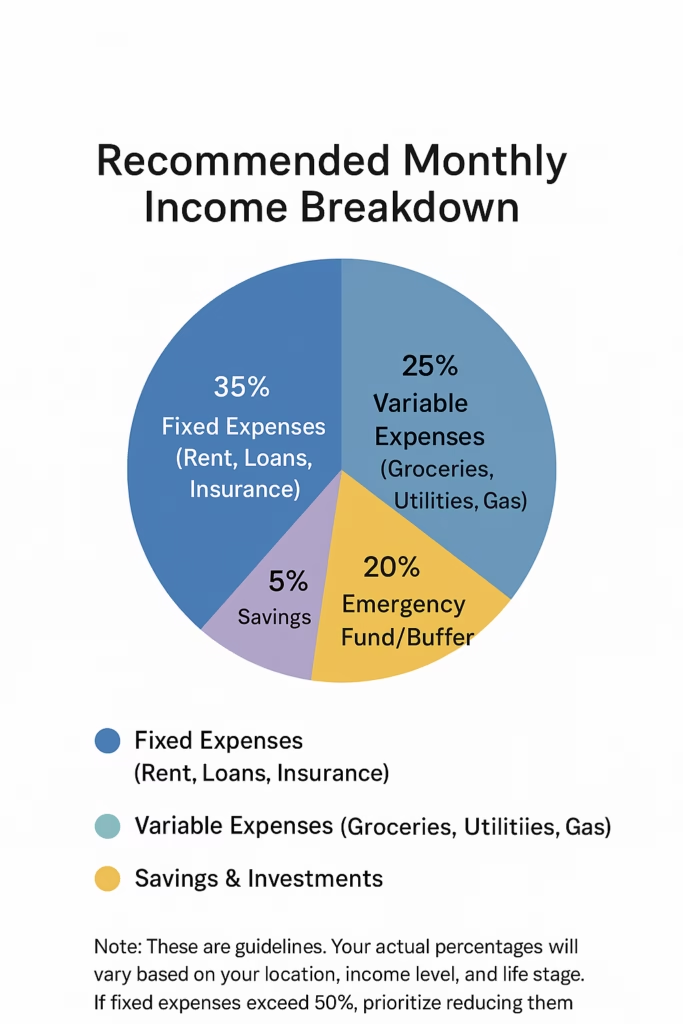

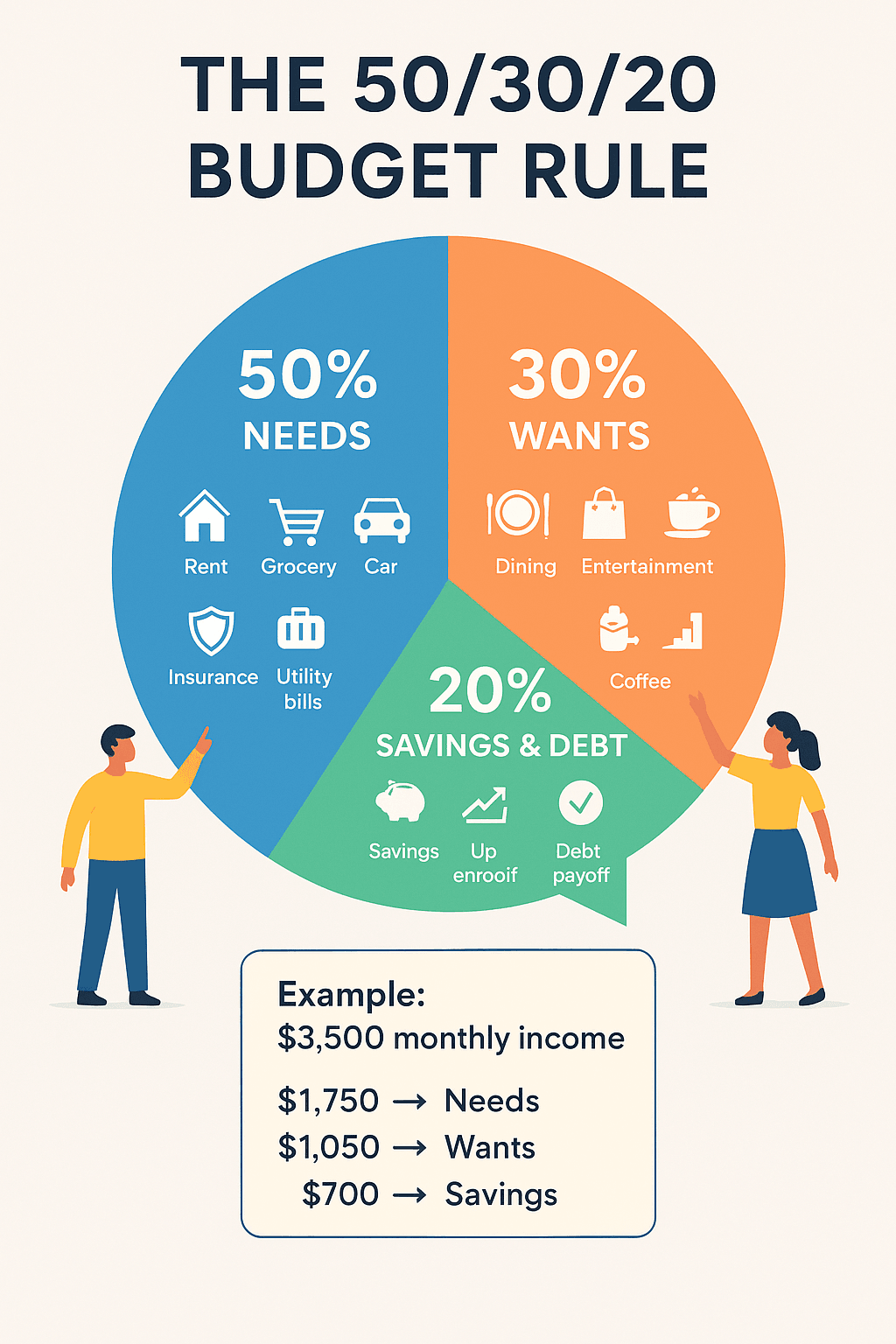

The framework:

50% of net income for needs (housing, food, utilities, minimum debt payments)

30% for wants

20% for savings and extra debt paydown

Pass threshold: Total debt payments shouldn’t exceed 36% of gross income. Housing should stay under 28%.

How to check:

(Total monthly debt payments ÷ Gross monthly income) × 100 = Your DTI percentage

Example:

Gross monthly income: $6,000

Mortgage: $1,500

Student loan: $400

Car payment: $350

Credit card minimums: $150

Total debt payments: $2,400

DTI: 40% → FAIL

You’re overleveraged. Don’t take on more debt.

💡 KEY INSIGHT: The 36% debt-to-income threshold isn’t arbitrary. It’s the point where financial stress typically begins affecting decision-making, health, and relationships. Stay below it.

Red flags:

You’re making minimum payments only. You’re using new debt to pay existing debt. You’re skipping other financial priorities to make debt payments. Money stress is constant.

Test #3: The Risk Test

The question: What happens when things go wrong?

Because they will. They always do eventually.

What to evaluate:

- Interest rate risk: Fixed or variable? If variable, can you afford a 3-4% increase?

- Income risk: If you lost your job tomorrow, how long could you make payments? Aim for 6+ months of coverage via emergency fund.

- Collateral risk: If the debt is secured, can you afford to lose the asset?

- Bankruptcy risk: Can you discharge this in bankruptcy if everything falls apart? Student loans generally can’t be.

- Co-signer risk: Are you putting someone else’s financial life at risk?

Pass threshold: You can handle at least two simultaneous risk factors without defaulting.

Example 1:

Fixed-rate federal student loan for nursing school.

- Income risk: LOW (nursing shortage, high demand)

- Interest rate risk: NONE (fixed rate)

- Discharge risk: LOW (high probability of repayment)

- Safety net: Income-driven repayment available

→ PASS (multiple protections)

Example 2:

Variable-rate private student loan for an arts degree.

- Income risk: HIGH (uncertain job market)

- Interest rate risk: HIGH (variable rate could spike)

- Discharge risk: HIGH (can’t discharge in bankruptcy)

- Safety net: None available

→ FAIL (too many unmitigated risks)

Test #4: The Time Horizon Test

The question: Does the debt term match how long the thing lasts or provides value?

You shouldn’t be paying for something after it’s worthless.

Pass threshold: Loan term should be ≤ 75% of useful life

Examples:

| Purchase | Useful Life | Acceptable Term | Typical Offers | Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home | 30+ years | 15-30 years | 30 years | Fine |

| Car | 10-12 years | 3-5 years | 6-8 years | Often excessive |

| Education | 40 years (career) | 10-20 years | 10-25 years | Usually okay |

| Furniture | 3-7 years | 1-2 years | 4 years | Outlasts value |

| Electronics | 2-4 years | 0 years | 2 years | Terrible idea |

| Vacation | Immediate | 0 years | 1-3 years | Absolutely not |

Red flag: Still paying for something that’s gone or worthless.

Example:

72-month car loan means you’re paying for six years. Most cars lose 60% of value in five years. You’ll owe more than it’s worth for years. If something happens to the car, you’re stuck with a loan for an asset you don’t have anymore.

Putting It All Together

Pass all four tests? The debt is probably fine.

Pass three? Proceed with extreme caution. Have backup plans.

Pass two or fewer? This is likely bad debt. Reconsider or find alternatives.

📋 DECISION FRAMEWORK:

- 4/4 tests passed: Green light (with normal caution)

- 3/4 tests passed: Yellow light (needs backup plans)

- 2/4 or fewer: Red light (find better alternatives)

Real decision: $200,000 for medical school

✓ ROI Test: Physician salary $200,000+ vs loan cost = positive ROI

✓ Cash Flow Test: Residency tight but physician income makes repayment feasible

✓ Risk Test: High job security, federal loans have protections

✓ Time Horizon Test: Career benefit lasts 30+ years, loans paid in 10-25 years

Verdict: Good debt (passes all tests with margins)

Real decision: $15,000 credit card for vacation

✗ ROI Test: Zero financial return

✗ Cash Flow Test: Minimum payments at 22% don’t make progress

✗ Risk Test: High interest, no protections, vulnerable to income disruption

✗ Time Horizon Test: Memories fade, debt lasts years

Verdict: Bad debt (fails everything)

Can Debt Build Wealth? Busting Dangerous Myths About Good Debt vs Bad Debt

Let’s kill some dangerous myths.

Because believing the wrong thing about debt? That’s how people end up broke.

Myth #1: “All Debt Is Bad”

This is oversimplified thinking that misses the strategic value of leverage.

If you can borrow at 4% to buy a home appreciating at 6% annually while investing savings in index funds returning 10%, you’re ahead using debt strategically.

Tying up $200,000 in cash for a home means sacrificing years of investment returns.

Example:

A business owner borrows $100,000 at 6% to expand operations generating 20% returns. They’re making 14% on other people’s money. That’s brilliant.

The key is “strategic.” Debt for appreciating assets or income-generating investments below your expected return creates wealth. Debt for consumption destroys it.

Myth #2: “Student Loans Are Always Worth It”

With average student loan debt at $39,547 and 9.4% of borrowers in default, clearly something isn’t working.

Critical factors:

- Field of study and realistic earnings

- Total debt vs expected starting salary

- Institution cost (they vary wildly for similar outcomes)

- Federal loans with protections vs private loans with none

- Actual job placement rates

$30,000 federal loan for engineering? Probably fine.

$120,000 private loan for uncertain career path? Dangerous.

Myth #3: “Homeownership Automatically Builds Wealth”

Not automatic at all.

Transaction costs eat 6-10% of value when buying and selling. Maintenance, insurance, property taxes add up. You need to stay put 5+ years minimum for appreciation to offset costs.

A $250,000 home appreciating 4% annually generates $10,000 in year one. But if you’re so house-poor you can’t contribute to retirement, you’re missing employer 401(k) matches potentially worth $12,000.

Net result? The “good debt” mortgage made you poorer.

Myth #4: “Always Pay Off Debt Early”

Depends on the interest rate and alternatives.

3% mortgage vs 10% stock market returns? Paying extra on the mortgage costs you 7% in opportunity cost. Invest instead.

22% credit card debt? Paying that off equals a guaranteed 22% return. That beats almost any investment.

Guideline:

- Debt above 7-8%: Pay off aggressively

- Debt 4-7%: Balance paydown and investing

- Debt below 4%: Consider investing extra money

Emotional factors matter too. If debt causes stress regardless of math, peace of mind has value beyond spreadsheets.

Myth #5: “Minimum Payments Are Manageable”

Minimum payments maximize bank profits, not your financial health.

$10,000 credit card at 22% APR making minimums:

- Takes 29 years to pay off

- Costs $16,305 in interest

- Total paid: $26,305 for a $10,000 balance

Double your payment: 5 years and $2,485 in interest.

Minimum payments keep you in debt forever.

Myth #6: “Buy Now Pay Later Isn’t Real Debt”

It’s absolutely real debt. Just invisible to credit bureaus.

BNPL creates the same obligations:

- You owe money

- Missing payments triggers fees and collections

- Multiple loans stack quickly

- Affects your ability to handle expenses

The invisibility makes it more dangerous, not less. You and potential lenders can’t see your full debt picture.

Myth #7: “Debt Consolidation Fixes Everything”

Consolidation treats symptoms, not causes.

Common pattern:

Carry $20,000 across five credit cards. Consolidate to one personal loan at lower rate. Feel relief at lower payment. Credit cards now available again. Slowly start using them. Two years later: consolidation loan plus $15,000 new credit card debt.

Consolidation is a tool, not a solution. The solution is spending less than you earn.

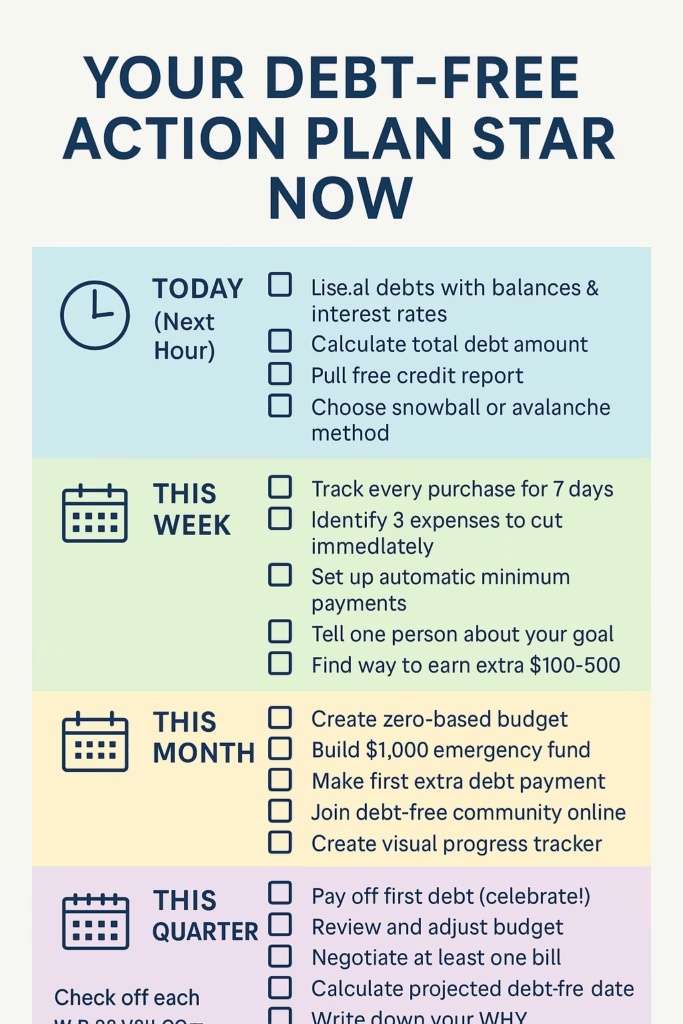

How to Actually Manage Debt Without Losing Your Mind

You’ve got debt. Now what?

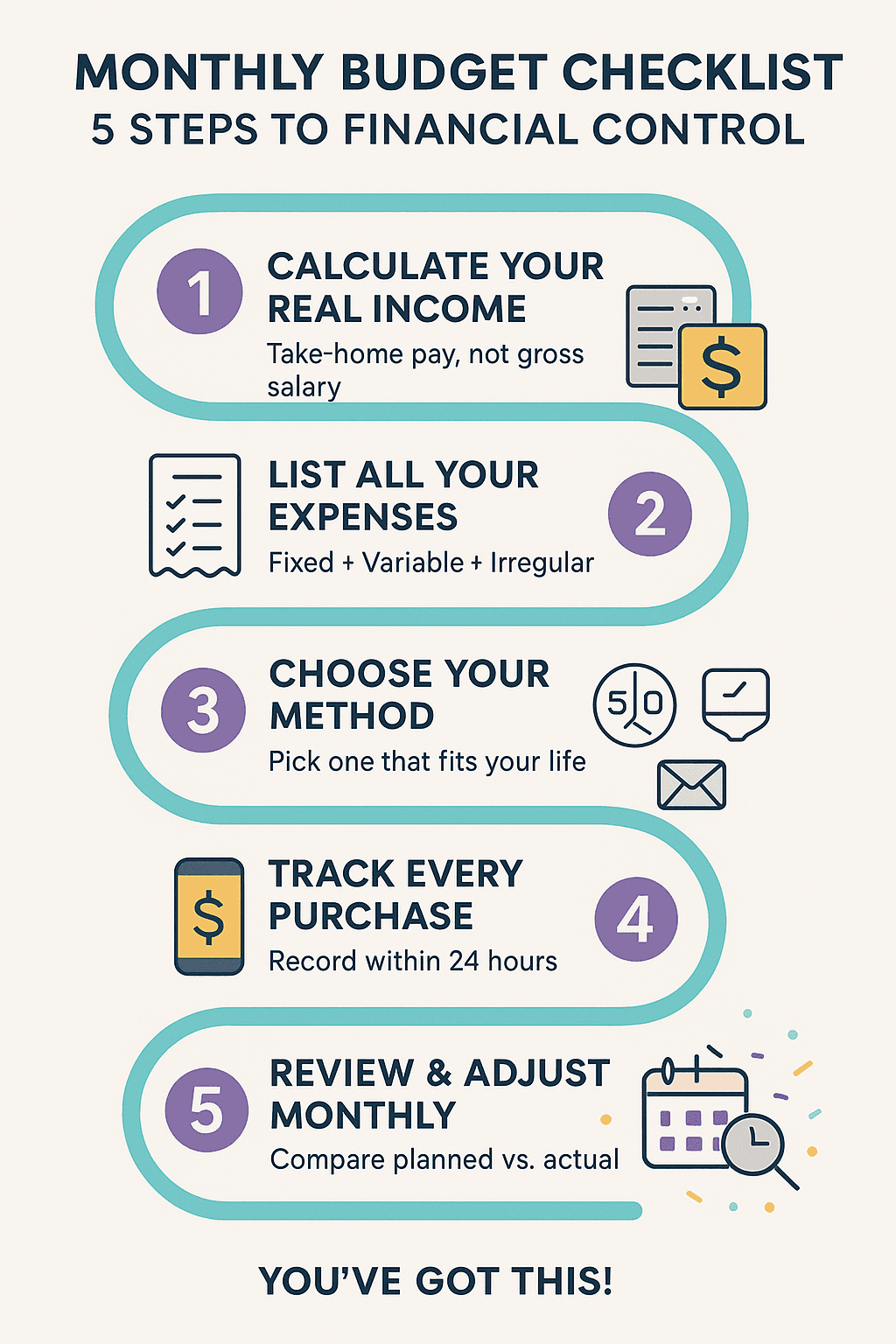

Step 1: Face It

You can’t fix what you won’t acknowledge.

Create a complete debt inventory. For each debt, list:

- Creditor name

- Current balance

- Interest rate

- Minimum monthly payment

- Payment due date

- Type (secured/unsecured, fixed/variable)

Most people are shocked when they see totals. That’s okay. Knowledge first.

I remember doing this myself years ago. The number was bigger than I expected. Seeing it all in one place felt terrible for about 24 hours. Then it became the starting line for actually fixing the problem.

Step 2: Prioritize Ruthlessly

Tier 1 – Emergency (handle immediately):

- Payday loans

- Debt in collections threatening wage garnishment

- Secured debt where you could lose essential assets

Tier 2 – High Priority (attack aggressively):

- Credit cards above 18% APR

- Private student loans above 8%

- Any debt affecting your mental health

Tier 3 – Medium Priority (consistent payments):

- Credit cards 15-18%

- Personal loans 8-15%

- Auto loans above 6%

Tier 4 – Low Priority (scheduled payments, don’t rush):

- Federal student loans below 6%

- Mortgage below 4%

- Any debt below 5% with tax benefits

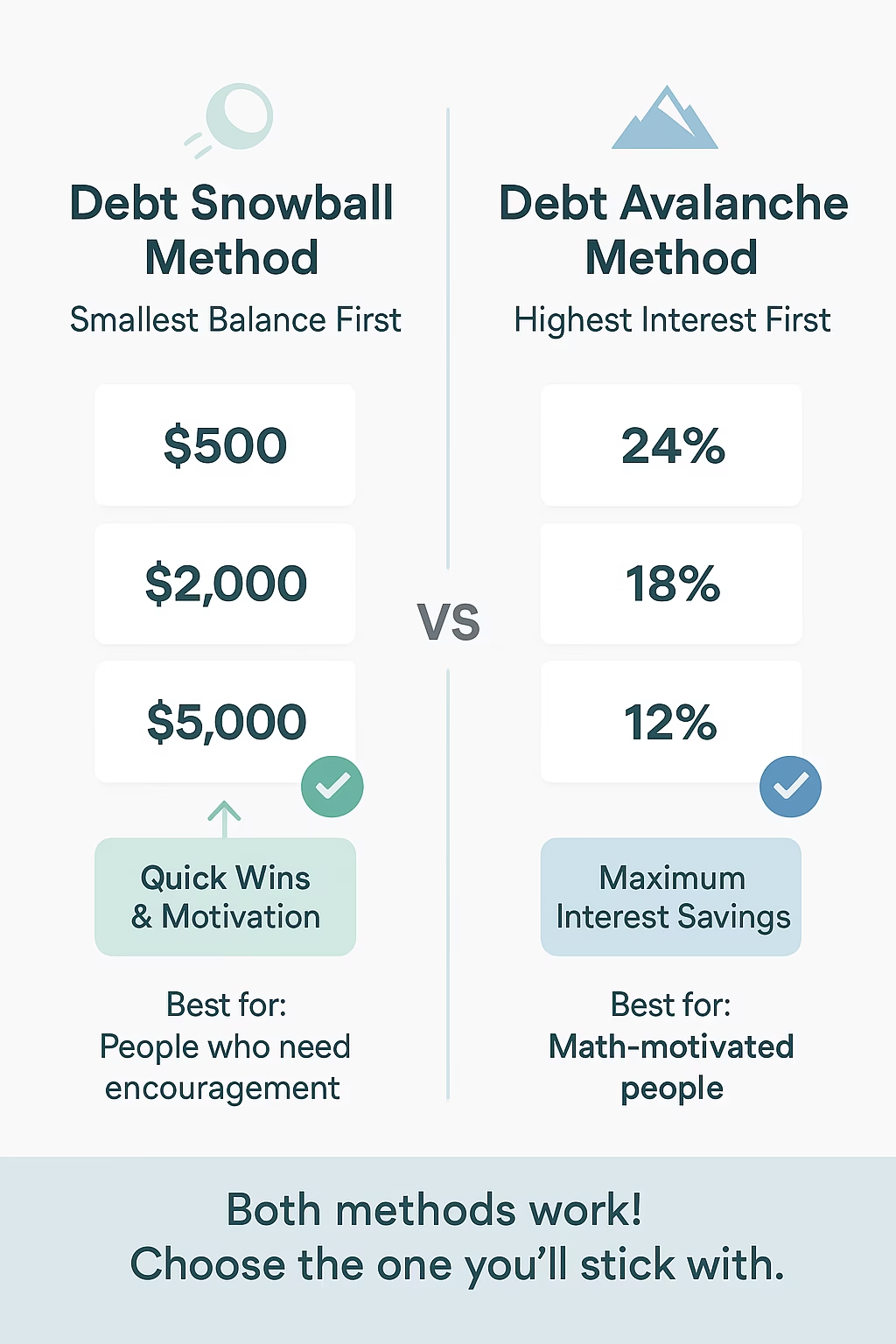

Step 3: Choose Your Strategy

Avalanche Method (mathematically optimal):

Pay minimums on everything. Put all extra money toward highest-interest debt first.

Saves the most in interest. Can feel slow if highest-interest debt has large balance.

Best for disciplined people motivated by optimization.

Snowball Method (psychologically motivating):

Pay minimums on everything. Put all extra money toward smallest balance first.

Quick wins boost motivation. May pay more total interest.

Best for people needing emotional wins.

Hybrid Approach (balanced):

Attack highest-interest debt first unless a small balance can be cleared in 2-3 months. Take that quick win, then return to avalanche.

Step 4: Find Extra Money

Low-hanging fruit:

- Cancel forgotten subscriptions (average person has 3-5)

- Negotiate lower insurance, phone, internet rates

- Sell unused items (average household has $7,000 worth)

- Request credit card rate reduction (83% successful)

- Redirect windfalls entirely to debt

Bigger moves:

- Downgrade housing temporarily

- Sell financed vehicle, buy reliable beater

- Pick up gig work specifically for debt elimination

Step 5: Stop the Bleeding

While paying off debt, you must stop accumulating new debt. Otherwise you’re bailing water from a sinking boat without plugging the hole.

Tactics:

- Remove credit cards from online shopping accounts

- Freeze cards in ice (sounds dumb, works brilliantly)

- Switch to cash for discretionary spending

- 48-hour rule for non-essential purchases

- Delete shopping apps

Address root cause:

- Spending exceeds income

- No emergency fund

- Emotional spending

- Lifestyle inflation

Step 6: Build Mini Emergency Fund

$1,000-$1,500 starter emergency fund.

Not your full emergency fund. Just enough to handle minor emergencies without new debt.

Temporarily pause aggressive payoff beyond minimums. Direct everything to savings until you hit the goal. Then resume aggressive payoff.

Feels counterintuitive but prevents the debt-payoff-debt-again cycle.

Step 7: Strategic Moves (With Caution)

Balance transfers:

0% APR cards for 15-21 months if you have good credit (680+).

Pay zero interest during promo, 100% of payments reduce principal.

Risks: 3-5% transfer fee, must pay off before promo ends, requires discipline.

Only if you have realistic payoff plan and won’t accumulate new debt.

Consolidation loans:

Combine multiple high-interest debts into one lower-rate loan.

Lower interest, single payment, fixed timeline.

Risks: May extend repayment, fees, freed-up credit tempts spending.

Only if math clearly saves money AND you address root spending problem.

Step 8: Protect Progress

Automate minimum payments. Track progress visually. Celebrate milestones modestly.

Join support communities. Reddit’s r/DaveRamsey, r/povertyfinance, r/DebtFree. Community accountability helps.

Your Questions Answered: Good Debt vs Bad Debt Examples Explained

Is student loan debt always good?

No. Not even close.

Student loans can be good when education significantly increases earnings and debt is manageable relative to expected income.

They become problematic when:

- Total debt exceeds first-year salary

- Degree field has limited prospects

- Interest rates high (private loans above 8%)

- You didn’t research actual employment outcomes

42.7 million Americans carrying average $39,547 federal loans with 9.4% delinquency proves not all student debt works out.

Is a mortgage always good debt?

Traditionally yes, but only within a healthy budget.

Problematic when:

- Housing costs exceed 28-30% of gross income

- Counting on appreciation to afford payments

- Variable rates could spike beyond affordability

- Using home equity for consumption

Historical appreciation around 6% annually makes mortgages powerful when used wisely. But 2008 proved not all mortgage debt is equal.

Is credit card debt always bad?

Almost always, yes—due to high rates averaging 22.3%.

Strategic credit card use isn’t bad though:

- Charge and pay in full monthly

- Collect rewards and cash back

- Use 0% APR periods with clear payoff plan

The moment you carry balance at standard APR, it becomes expensive bad debt.

Exception: Strategic balance transfers to 0% cards, but only if you stop accumulating debt and commit to payoff.

What type of debt is considered good debt?

Good debt typically has these characteristics:

- Interest rate under 7-8%

- Used to acquire assets that appreciate or generate income

- Comes with tax benefits

- Has reasonable repayment terms

- Fits comfortably within your budget

Examples include mortgages on affordable homes, federal student loans for high-ROI degrees, business loans that generate revenue exceeding costs, and certain investment loans.

But remember: the category alone doesn’t make it good. Your specific situation determines whether that debt serves you or hurts you.

Can you build wealth with debt?

Yes, but only with strategic use of good debt.

Wealthy people and businesses use debt as leverage. They borrow at low rates to invest in assets returning higher rates. The difference builds wealth.

Examples:

- Mortgage at 4% while home appreciates at 6%

- Business loan at 6% funding expansion generating 20% returns

- Investment property loan at 5% with 8% rental yield

The key: the debt must create value exceeding its cost. And you must manage risk carefully. Leverage amplifies gains but also losses.

How much debt is too much?

Financial advisors recommend total debt payments below 36% of gross income, housing under 28%.

But context matters:

- Type of debt: $50K student loans for physician is manageable, $50K credit cards is crisis

- Interest rates matter

- Income stability matters

- Other obligations matter

Warning signs:

- Making minimums only

- Using new debt to pay existing debt

- Constant money stress

- One missed paycheck causes defaults

- Can’t save anything

How do beginners manage debt wisely?

Start here:

- Inventory everything

- Create realistic budget

- Stop accumulating new debt

- Build $1,000-$1,500 emergency fund

- Choose payoff strategy (avalanche or snowball)

- Automate minimum payments

- Attack one debt aggressively while maintaining minimums on others

- Track and celebrate progress

Consistency beats perfection. Small sustained progress beats sporadic heroic efforts that burn out.

Final Verdict on Good Debt vs Bad Debt in 2026

Here’s the truth most finance articles won’t tell you.

The label “good debt” or “bad debt” matters less than how you use it and whether it serves your actual financial goals.

A mortgage can build generational wealth or keep you cash-poor for decades.

Student loans can be smart investments or 20-year burdens without corresponding income growth.

Even credit cards can be used strategically or become financial disasters.

The difference? Intention. Mathematics. Honesty.

Before taking on debt in 2026, ask yourself:

- Does this have positive ROI exceeding its cost?

- Can I comfortably afford payments in a balanced budget?

- What happens if things go wrong?

- Does debt term match asset/benefit lifespan?

Can’t answer confidently? Pause. The opportunity will either still be there after you’ve done your homework, or it wasn’t the right opportunity anyway.

For those managing debt now: progress compounds like interest does.

Every extra dollar toward high-interest debt is money you’re not paying banks. Every month of consistent payments builds momentum. Every cleared balance deserves celebration.

The financial system profits from confusion and impulse. Your power comes from clarity, strategy, patience.

Understanding good debt vs bad debt examples isn’t about following absolute rules. It’s about making informed choices aligned with your values and goals.

Can debt build wealth? Absolutely—when used strategically with clear ROI and managed carefully.

Can “good debt” destroy your finances? Unfortunately, yes—when you overleverage or circumstances change.

The key is knowing how to evaluate each borrowing decision using real frameworks, not marketing or social pressure.

Take control of your debt. Don’t let it control you.

Small consistent actions create financial freedom.

You’ve got this.

Important Legal Stuff

This article provides general educational information about debt and personal finance. It’s not personalized financial, legal, or investment advice.

Your situation is unique. What works for one person may be wrong for another.

Before major financial decisions, consult qualified professionals:

- Certified Financial Planner (CFP)

- Credit counselor (National Foundation for Credit Counseling)

- Tax advisor

- Attorney for legal implications

Market conditions, rates, tax laws, regulations change constantly. This was last updated February 2026. Verify current information before decisions.

Examples are illustrative. Your results will differ. Past performance doesn’t guarantee future outcomes.

If experiencing financial hardship:

- National Foundation for Credit Counseling: 1-800-388-2227

- Financial Counseling Association of America

- Local community assistance

- Your lender’s hardship department

Getting help early prevents small problems from becoming disasters. No shame in seeking assistance.

Ready to take control? Use the 4-Test Framework on any borrowing decision you’re considering right now. Create your debt inventory if you haven’t. Pick a payoff strategy and commit for 90 days.

Start today. Not tomorrow. Today.