Self-Employment Tax for Freelancers: The Real-Talk Guide to Keeping More of What You Earn (Without the IRS Panic)

I’ll never forget opening my first big freelance check: $5,000 for a month-long project. I felt like I’d finally “made it.” Fast forward to April, and my accountant dropped the news—I owed nearly $2,000 in taxes I hadn’t set aside. Cue the panic, the Googling at 2am, and the frantic scramble to figure out what self-employment tax even meant.

Here’s what nobody tells you when you start freelancing: you’re not just paying income tax anymore. You’re also covering the full 15.3% self-employment tax that used to be split with your employer. That’s Social Security and Medicare—the same FICA deductions you saw on old pay stubs, except now you’re paying both sides of the bill.

But here’s the good news: once you understand how self-employment tax actually works and set up a simple system to save for quarterly estimated taxes, you’ll never have that “oh crap” moment again. This guide walks you through everything—the calculations, the deadlines, the savings strategies, and the mistakes to avoid—in plain English, based on 2025 IRS rules.

Table of Contents

- What Is Self-Employment Tax and Why Does Everyone Freak Out About It?

- How to Calculate Self-Employment Tax for the First Time (Without Your Brain Melting)

- Understanding Quarterly Estimated Taxes: The Payment Schedule That Actually Makes Sense

- The Simple System for Saving Quarterly Taxes from Each Payment

- Common Mistakes and How to Avoid an IRS Underpayment Penalty

- Self-Employment Tax Deductions You Actually Qualify For (2025 Rules)

- IRS Schedule SE Explained for Beginners

- Compliance Reminder: The Boring But Important Stuff

- FAQs: Your Burning Questions Answered

- Final Thoughts: You’ve Got This

What Is Self-Employment Tax for Freelancers and Why Does Everyone Freak Out About It?

Remember when you had a “real job” and your paycheck was always less than you expected? You’d glance at your pay stub and see mysterious deductions labeled “Social Security” and “Medicare”—together called FICA taxes. Your employer was taking 7.65% from your check, and quietly paying another 7.65% on your behalf. Nice of them, right?

When you become self-employed—whether you’re freelancing, consulting, or running a side hustle—you become both the employee AND the employer. Which means you’re now responsible for the entire 15.3%. It breaks down like this:

- 12.4% for Social Security (on your first $176,100 of net earnings in 2025)

- 2.9% for Medicare (on all net earnings, no cap)

- Plus an extra 0.9% Medicare surtax if you earn over $200,000 ($250,000 for married couples)

Think of it like splitting dinner with a friend who conveniently “forgot” their wallet when the check comes. Suddenly you’re covering both meals—not just yours.

The W-2 vs. Self-Employed FICA Breakdown

| Tax Component | W-2 Employee | Self-Employed |

|---|---|---|

| Social Security (12.4%) | You pay 6.2%, employer pays 6.2% | You pay full 12.4% |

| Medicare (2.9%) | You pay 1.45%, employer pays 1.45% | You pay full 2.9% |

| Total FICA | 7.65% (your share) | 15.3% (both shares) |

| Who handles it | Employer auto-withholds | You calculate & pay quarterly |

The upside? You get to deduct half of your self-employment tax when calculating your income tax. It’s the IRS’s way of acknowledging you’re playing both roles. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Related topic: Guide to tax filling

How to Calculate Self-Employment Tax for First Time Freelancers (Without Your Brain Melting)

Look, I’m not going to lie to you—the first time you do this, it feels like you need a PhD in tax law. But once you understand the flow, it’s actually pretty straightforward. Here’s the exact process:

Step 1: Figure Out Your Net Earnings (Not Just What You Made)

Your net earnings = Total income – Business expenses

This is crucial: you don’t pay self-employment tax on your gross income. You pay it on your profit after legitimate business expenses. This is where keeping good records pays off—literally.

What counts as a business expense?

- Home office (if you have a dedicated workspace)

- Internet and phone (business portion)

- Software subscriptions (Canva, Adobe, project management tools)

- Business mileage (70 cents per mile in 2025)

- Professional development (courses, conferences)

- Health insurance premiums (if you’re not eligible for coverage elsewhere)

- Equipment, supplies, and tools you need to do your work

You’ll calculate this net profit on Schedule C when you file your taxes. For now, just know: expenses = lower taxes.

Step 2: Apply the Magic 92.35% Multiplier

Here’s where it gets a little weird (but in a good way). You don’t actually pay self-employment tax on 100% of your net earnings. The IRS lets you deduct the employer-equivalent portion first.

The calculation: Net earnings × 0.9235

Why 92.35%? Because the IRS is acknowledging that employers get to deduct their half of FICA as a business expense. You should too. It levels the playing field.

Example:

Let’s say you earned $60,000 in net profit after expenses.

$60,000 × 0.9235 = $55,410 (this is what you’ll actually calculate tax on)

Step 3: Calculate Your Actual Self-Employment Tax

Now multiply your adjusted net earnings by 15.3%.

Using our example:

$55,410 × 0.153 = $8,477.73

That’s your total self-employment tax bill for the year.

Step 4: Don’t Forget—You Get to Deduct Half

Here’s the silver lining: you can deduct 50% of your self-employment tax when calculating your adjusted gross income (AGI). This doesn’t reduce your self-employment tax itself, but it does reduce your income tax.

In our example:

You’d deduct $4,238.87 (half of $8,477.73) on your Form 1040, which lowers the income amount subject to federal and state income taxes.

Bottom line for a $60,000 freelance income:

- Self-employment tax owed: ~$8,478

- Income tax deduction you get: ~$4,239

- Effective self-employment tax rate: closer to 14.1% after the deduction

Still feels like a lot? It is. But remember—W-2 employees were also paying this, they just never saw it because it was hidden in their pay stub.

Understanding Quarterly Estimated Taxes for Self-Employed Workers: The Payment Schedule That Actually Makes Sense

Here’s where the IRS throws everyone for a loop: they don’t wait until April 15th to collect taxes. They expect you to pay as you earn throughout the year, which means making estimated tax payments every quarter.

Why? Because the U.S. tax system is “pay-as-you-go.” Employers withhold taxes from every paycheck. You don’t have that, so you need to do it yourself.

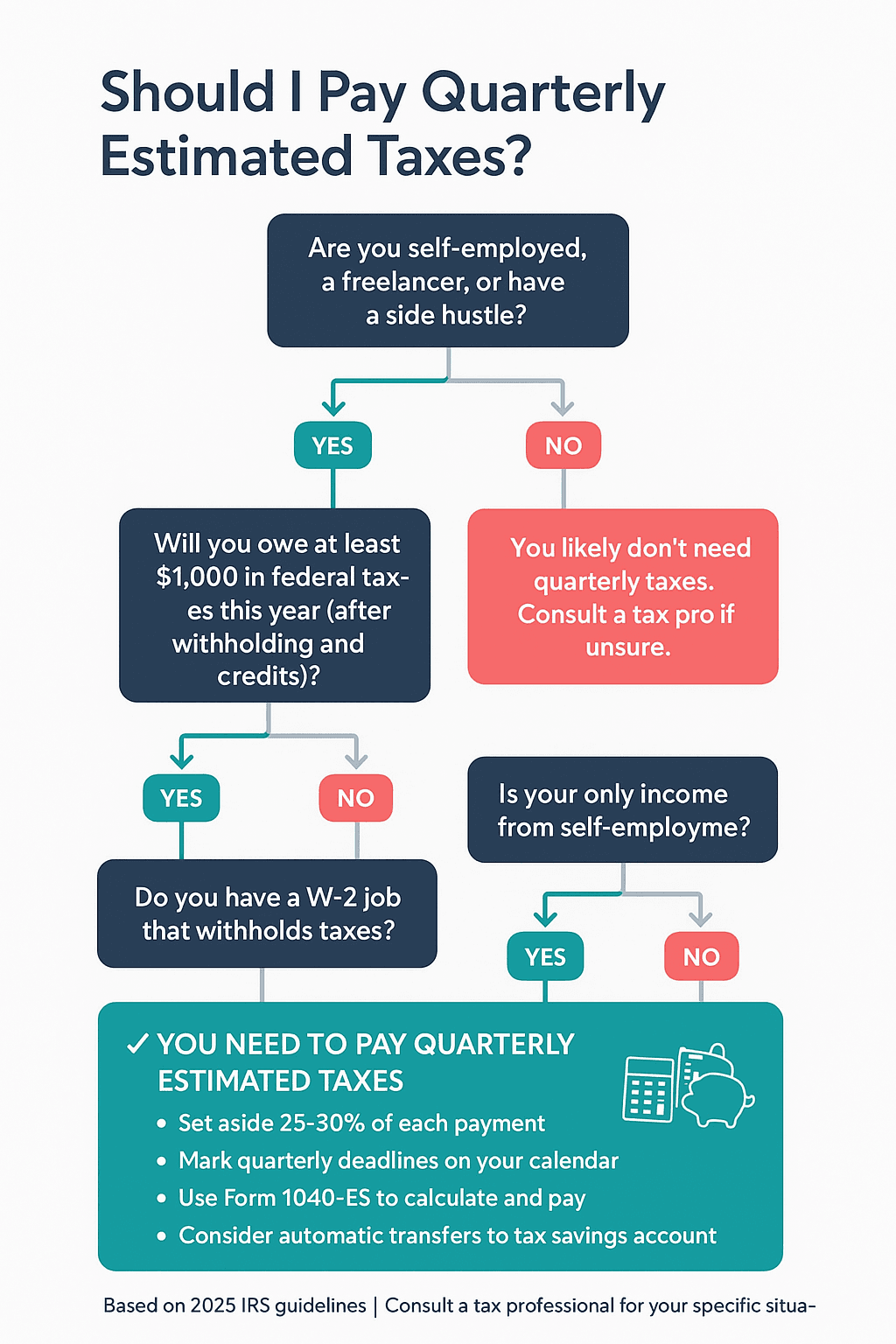

Who Needs to Pay Quarterly Taxes?

You need to make quarterly payments if:

- You expect to owe at least $1,000 in federal taxes this year (after accounting for any withholding and credits)

- You’re earning more than modest side income as a freelancer

For most people earning more than $10,000-$15,000 annually from self-employment, you’ll hit this threshold.

The 2025 Quarterly Payment Deadlines (Mark Your Calendar Now)

Here’s the confusing part: they’re called “quarterly” but they’re not actually three-month periods. The tax year is divided into four unequal chunks:

| Quarter | Income Period | Payment Due Date |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | January 1 – March 31 | April 15, 2025 |

| Q2 | April 1 – May 31 | June 16, 2025 |

| Q3 | June 1 – August 31 | September 15, 2025 |

| Q4 | September 1 – December 31 | January 15, 2026 |

If a due date falls on a weekend or federal holiday, your payment is due the next business day.

Notice something odd? Q2 is only two months, and Q4 is only three-and-a-half months. Nobody said the tax code makes sense.

How to Calculate What You Actually Owe Each Quarter

You have two main approaches, and which one you choose depends on your situation:

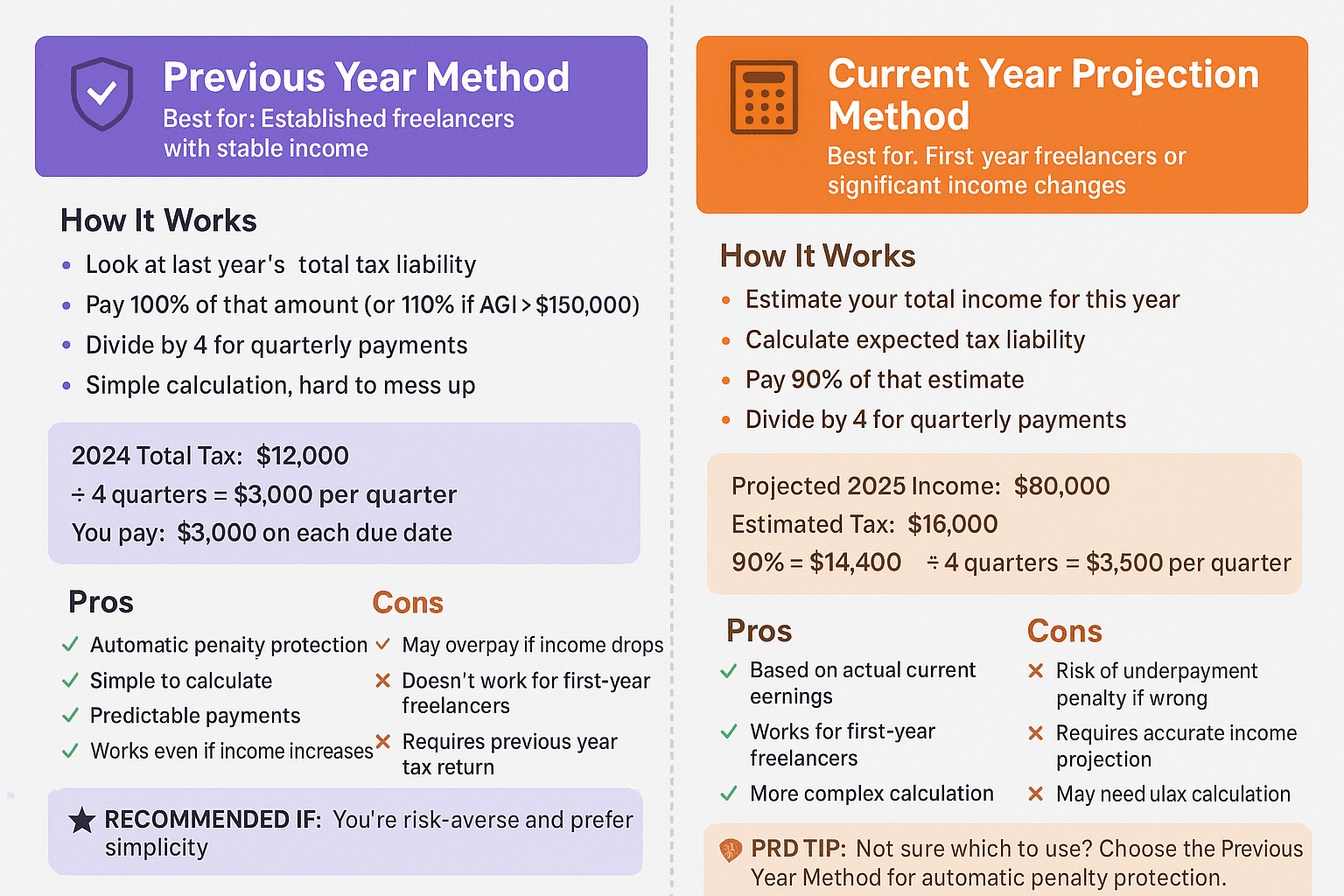

Method 1: The Previous Year Method (Recommended for most people)

Look at last year’s total tax bill (line 24 on your Form 1040). Calculate 100% of what you owed, divide by four, and pay that amount each quarter.

The safe harbor rule: If your adjusted gross income was over $150,000, you need to pay 110% of last year’s tax instead of 100%.

Why this works: Even if your income shoots up dramatically this year, you won’t face penalties as long as you paid 100% (or 110%) of last year’s total tax. You’ll owe the difference when you file, but no penalties.

Example:

2024 total tax: $12,000

÷ 4 = $3,000 per quarter

You pay $3,000 on each deadline, no matter what you actually earn this year.

Method 2: The Current Year Projection Method

Estimate your total income for this year, calculate your expected tax bill (both self-employment and income taxes), and divide by four.

When to use this: If you’re in your first year of freelancing (no previous year to reference), or if your income dropped significantly.

Example:

Projected 2025 income: $80,000

Estimated total tax: $16,000

90% minimum = $14,400

÷ 4 = $3,600 per quarter

The catch: If you underestimate, you risk underpayment penalties. Be conservative.

Need help with the actual calculations? The IRS provides detailed worksheets and payment vouchers on the official Form 1040-ES page. The form walks you through estimating your income, calculating deductions, and figuring out exactly how much to pay each quarter. It even includes vouchers if you’re mailing checks (though I’d recommend electronic payment—more on that later).

The Simple System for Saving Quarterly Taxes from Each Payment (The Method That Actually Works)

Here’s the truth: understanding the tax calculations is great. But if you don’t have a system to actually set the money aside, you’ll still end up scrambling when quarterly deadlines hit.

This is where most freelancers fail. They see a $4,000 payment hit their bank account and think, “I made $4,000!” Then three months later, they realize they should have set aside $1,200 for taxes but spent it on rent, groceries, or that “business expense” dinner that was 80% social.

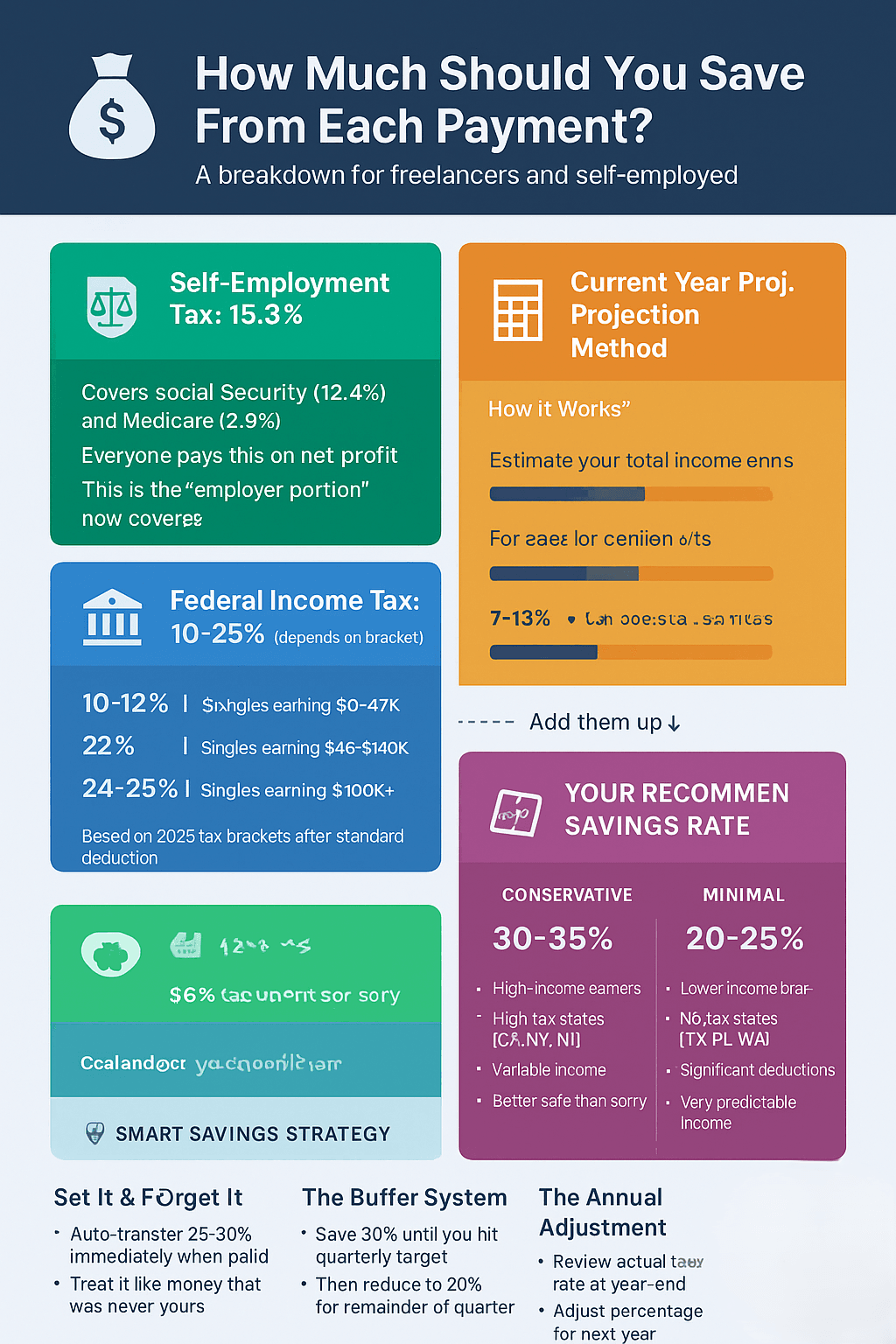

The Automatic Transfer Method (The One I Wish I’d Used from Day One)

Here’s what you do:

- Open a separate savings account called “Tax Savings” or “Quarterly Taxes”—make it completely separate from your emergency fund or personal savings.

- Set up an automatic rule: Every time a client payment hits your business checking account, immediately transfer 25-30% to your tax account.

Why 25-30%?

- 15.3% covers self-employment tax

- 10-15% covers a reasonable estimate for federal income tax (depending on your bracket)

- Add more if you’re in a high-tax state like California or New York

Example:

$2,000 client payment arrives → $600 automatically transfers to tax savings

$5,000 project payment → $1,500 goes to taxes

You never see that money as “spendable,” which removes the temptation entirely.

Pro tip: Many business banking apps (like Novo, Relay, or even QuickBooks) let you set up percentage-based automatic transfers. When money arrives, a portion instantly moves. Set it once, forget about it.

The Monthly Reconciliation Method (For Irregular Income)

If your income is all over the place—$10,000 one month, $1,500 the next—try this:

On the 1st of every month:

- Look at what you earned last month

- Calculate 25-30% of that total

- Transfer it to your tax savings account

This creates a predictable rhythm without dealing with each individual payment.

The “Pay Yourself First” Modification (Advanced)

Once you get comfortable, try this hybrid approach:

Here’s how it works:

- Calculate your estimated quarterly payment (let’s say $4,000)

- Add a 15% buffer ($4,600)

- Save 30% of each payment until you hit $4,600

- Once you reach that amount, reduce your savings rate to 20% for the rest of the quarter

- On April 1st (or the start of the next quarter), reset and start building toward the next payment

Example:

By mid-February, you’ve saved $5,000 for your April 15th payment (you only need $4,000).

For March payments, you can reduce your tax savings to 20% since you’re already covered.

Come April, reset to 30% and start building for June.

The Spreadsheet Safety Net (15 Minutes a Month = Zero Panic)

Create a simple tracker (Google Sheets works great) with these columns:

| Date | Income Received | Amount Saved (30%) | Tax Account Balance | Quarterly Payment Made | Balance Remaining |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feb 15 | $3,000 | $900 | $900 | – | $900 |

| Mar 1 | $2,000 | $600 | $1,500 | – | $1,500 |

| Mar 20 | $5,000 | $1,500 | $3,000 | – | $3,000 |

| Apr 15 | – | – | $3,000 | $3,000 | $0 |

Update it monthly. This 15-minute habit gives you total peace of mind and catches problems before they become crises.

What If Your Income Varies Wildly? (Seasonal Freelancers, This Is for You)

Maybe you’re a wedding photographer who earns $20,000 in May and $800 in January. Or a consultant with project-based income that’s feast or famine.

Two strategies:

Option 1: The Annualized Income Installment Method

The IRS actually allows you to calculate each quarterly payment based on your actual income for that specific period, rather than dividing your annual estimate by four. You’ll use Form 2210 Schedule AI at tax time to prove you don’t owe penalties.

When November is huge but February is dead, this prevents you from overpaying early in the year.

Most tax software (TurboTax, TaxAct, FreeTaxUSA) can handle these calculations if you input your income by quarter.

Option 2: The Conservative Baseline Approach

Save aggressively when money is good to cover lean periods.

Example:

August: $12,000 project lands → Set aside $4,000 immediately

December: Only earned $2,000 → You already have a cushion, no scrambling needed

Your tax savings account becomes your buffer for slow months.

Avoiding IRS Underpayment Penalty as a Freelancer: Common Mistakes and How to Stay Safe

Let’s talk about the thing that keeps new freelancers up at night: the underpayment penalty.

The IRS charges penalties if you don’t pay enough tax throughout the year—even if you settle up in full by April 15th. It’s basically interest on the amount you should have paid during each quarter but didn’t.

The Safe Harbor Rules That Protect You (Your Get-Out-of-Jail-Free Card)

You will NOT be charged an underpayment penalty if you meet any of these conditions:

- You pay at least 90% of the tax you owe for the current year, OR

- You pay 100% of the tax you owed for the previous year (110% if your previous year’s AGI was over $150,000), OR

- You owe less than $1,000 in tax after subtracting withholdings and credits

This is your safety net. Most freelancers use option #2—the “previous year method.” Even if your income doubles this year, as long as you paid 100% (or 110%) of last year’s total tax bill, you’re protected from penalties. You’ll owe the difference when you file, but no penalty.

Mistake #1: Not Paying Anything Until April

The problem: The IRS expects you to pay taxes as you earn income. If you wait until April 15th to pay your entire annual tax bill, you’ll face underpayment penalties for all four quarters—even though you technically paid everything by the deadline.

The fix: Make quarterly payments throughout the year. Set calendar reminders for those four deadlines.

Mistake #2: Drastically Underestimating Your Income

The problem: You project earning $40,000 but actually earn $80,000. Your quarterly payments were based on the lower estimate, so you didn’t pay 90% of your actual tax.

The fix: If you land a big project mid-year, recalculate and adjust your remaining quarterly payments upward. Don’t wait until the end of the year to catch up.

Mistake #3: Missing a Quarterly Deadline

What happens: Life happens. Projects fall through, clients pay late, or you simply forget.

The damage: The penalty is calculated separately for each quarter, based on how much you underpaid and for how long. Each missed quarter accrues its own penalty.

The fix: If you miss a payment, pay as soon as you realize it. Don’t wait until the next quarter. Paying late is better than not paying at all. You can’t erase a quarter’s penalty by overpaying in a later quarter, but you can minimize the damage by catching up quickly.

Mistake #4: Treating the Tax Savings Account Like a Bonus Slush Fund

The problem: You diligently save 30% of each payment, then see $8,000 sitting in your tax account in March and think, “I could really use a new laptop…”

The fix: That money is not yours. It belongs to the IRS. Treat your tax savings account as completely off-limits except for making quarterly payments. If you dip into it for “emergencies,” you’re just setting yourself up for panic in April.

Mistake #5: Not Adjusting When Income Drops

The problem: You paid $12,000 in taxes last year. This year, you’re on track to earn 40% less due to a slow market, but you’re still paying $3,000 per quarter based on last year’s numbers.

The fix: You’re allowed to reduce your quarterly payments to reflect your new income projection. The IRS doesn’t require you to overpay. Just be conservative in your estimates to avoid underpayment penalties.

Self-Employment Tax Deduction Rules 2025: What You Can Actually Write Off (And What You Can’t)

One of the few perks of self-employment? A much bigger universe of deductions. Every legitimate business expense reduces your net profit, which reduces both your self-employment tax and your income tax.

But here’s the thing: the IRS has rules. You can’t just write off your Netflix subscription because you “watch it while working.” (Trust me, people try.)

The Golden Rule: Ordinary and Necessary

The IRS says expenses must be:

- Ordinary: Common and accepted in your field

- Necessary: Helpful and appropriate for your business (doesn’t have to be “essential,” just relevant)

Example:

If you’re a graphic designer, Adobe Creative Cloud is ordinary and necessary.

If you’re a freelance writer, a $3,000 camera probably isn’t (unless you also do photography).

The Big Deductions Worth Knowing

1. The Home Office Deduction

If you have a dedicated space used exclusively and regularly for business, you can deduct a portion of your rent/mortgage, utilities, internet, and home insurance.

Two methods:

- Simplified method: $5 per square foot, up to 300 square feet (max $1,500)

- Actual expense method: Calculate the percentage of your home used for business, apply it to all qualifying expenses

Example:

Your home office is 150 sq ft in a 1,000 sq ft apartment (15% of total space).

Monthly rent: $2,000 → You can deduct $300/month ($3,600/year)

Plus 15% of utilities, internet, renters insurance, etc.

The catch: That space needs to be used exclusively for business. Your kitchen table doesn’t count if you also eat dinner there.

2. The Self-Employment Tax Deduction (The One Everyone Forgets)

You can deduct 50% of your self-employment tax when calculating your adjusted gross income.

Why this matters: This is an “above-the-line” deduction, meaning you don’t need to itemize to claim it. It directly reduces your taxable income.

Example:

You paid $8,000 in self-employment tax.

You can deduct $4,000 from your income.

If you’re in the 22% tax bracket, that saves you $880 in federal income tax.

3. Health Insurance Premiums

If you’re paying for your own health insurance (and you’re not eligible for coverage through a spouse’s employer), your premiums are fully deductible.

Example:

Monthly premium: $600

Annual deduction: $7,200

This is huge. Health insurance is expensive for self-employed folks, and this deduction makes a meaningful dent.

4. Retirement Contributions (SEP IRA, Solo 401(k))

Contributions to self-employed retirement accounts are deductible and help you build long-term wealth.

For 2025:

- SEP IRA: You can contribute up to 25% of your net self-employment earnings, with a max of $69,000

- Solo 401(k): Similar limits, plus you can make employee deferrals up to $23,000 (or $30,500 if you’re 50+)

Example:

Net earnings: $80,000

SEP IRA contribution: $20,000

Tax savings (22% bracket): $4,400

Plus, you just saved $20,000 for retirement. Win-win.

5. Business Expenses (The Long List)

These all count if they’re ordinary and necessary for your work:

- Software subscriptions (Zoom, Slack, Notion, Canva, Adobe, etc.)

- Professional development (courses, books, conferences, coaching)

- Business insurance (liability, E&O, etc.)

- Office supplies and equipment

- Business mileage (70 cents per mile in 2025 using standard mileage rate)

- Bank fees and merchant processing fees

- Legal and professional fees (CPA, lawyer)

- Advertising and marketing

- Website hosting and domain fees

- Contract labor (if you hire subcontractors or VAs)

Pro tip: Track EVERYTHING. Even small expenses add up. Use an app like QuickBooks Self-Employed, Keeper Tax, or even a simple spreadsheet.

What You CAN’T Deduct (Don’t Try It)

- Personal meals (unless you’re traveling for business)

- Commuting from home to a workplace (though driving to client meetings IS deductible)

- Clothing, unless it’s a uniform or protective gear not suitable for everyday wear

- Gym memberships (unless you’re a fitness professional)

- Entertainment expenses (these were eliminated in 2018)

The bottom line: When in doubt, ask yourself: “Is this expense directly related to earning income?” If yes, it’s probably deductible. If it’s a gray area, consult a tax pro.

Want the official word on what’s deductible? The IRS breaks down all the rules, rates, and requirements on their Self-Employment Tax information page. It’s worth bookmarking for reference when you’re wondering whether something qualifies as a legitimate business expense.

IRS Schedule SE Explained for Beginners (It’s Not as Scary as It Looks)

Okay, let’s talk about Schedule SE (Self-Employment Tax)—the actual form you’ll use to calculate and report these taxes to the IRS.

First, the good news: Schedule SE is basically a worksheet. It walks you through the exact steps we covered earlier. Most of the time, you won’t even see it because your tax software does all the math automatically.

But it’s worth understanding what’s happening behind the scenes.

What Is Schedule SE?

Schedule SE is how you calculate the self-employment tax you owe and report it to the IRS. If your net self-employment income is $400 or more, you must file this form.

The Two Parts of Schedule SE

Part I: Self-Employment Tax (Short Schedule)

This is where most freelancers and sole proprietors do their calculations. It’s the simplified version.

Part II: Optional Methods

This section contains alternative calculations for farmers and people with very low earnings (under $7,240 for 2025). Most freelancers won’t need this.

How Schedule SE Actually Works (Line by Line)

Line 2: Your net profit from Schedule C (your freelance income minus expenses)

Line 3: Multiply line 2 by 0.9235 (the 92.35% we talked about earlier)

Line 4: Multiply line 3 by 0.153 (that’s your 15.3% self-employment tax rate)

Line 6: This is your total self-employment tax (this number goes to your Form 1040)

Line 7: Deduct half of your self-employment tax (this reduces your taxable income)

That’s it. The form does all the heavy lifting. You just plug in numbers and multiply.

Do You Actually Have to Fill This Out Yourself?

Not really. If you’re using tax software like TurboTax, FreeTaxUSA, or TaxAct, the program automatically generates Schedule SE based on the income and expenses you enter. You’ll barely notice it’s happening.

When to fill it out manually: If you’re filing a paper return or want to understand the mechanics before trusting software.

Pro tip: Even if software does it for you, review the final Schedule SE before submitting. Make sure the numbers make sense and match your records.

Compliance Reminder: The Boring But Important Stuff

📋 IMPORTANT TAX DISCLAIMER

This guide is based on 2025 IRS guidelines and is intended for educational purposes. Tax laws change, and individual situations vary.

You should:

- Consult with a qualified CPA, Enrolled Agent, or tax professional for advice specific to your situation

- Keep detailed records of all income and expenses

- Save receipts, invoices, and bank statements for at least 7 years

- Review IRS publications (like Publication 334 for small businesses) for official guidance

When to get professional help:

- Your income exceeds $100,000 annually

- You have multiple income streams or business entities

- You’re forming an LLC, S-corp, or hiring employees

- You’re unsure about major deductions or classifications

- You received or sent international payments

The cost of professional help (which is tax-deductible!) often pays for itself through discovered deductions and avoided penalties.

FAQs: Your Burning Questions About Self-Employment Taxes Answered

How do I calculate self-employment tax for the first time if I have no previous year to reference?

Great question—this is the situation every new freelancer faces. Here’s what you do:

- Estimate your total income for the year. Be realistic but slightly conservative. Look at your current contracts, pipeline, and average monthly earnings so far.

- Subtract estimated business expenses (typically 20-40% of gross income depending on your field).

- Calculate your projected net profit.

- Multiply by 0.9235 to get your adjusted net earnings.

- Multiply by 0.153 to get your self-employment tax.

- Add your estimated income tax (use the IRS tax brackets for 2025).

- Divide your total estimated tax by 4 to get your quarterly payment amount.

Example:

Projected gross income: $60,000

Estimated expenses: $15,000

Net profit: $45,000

Adjusted earnings: $45,000 × 0.9235 = $41,557

SE tax: $41,557 × 0.153 = $6,358

Income tax (22% bracket): ~$5,500

Total estimated tax: ~$11,858

Quarterly payment: $11,858 ÷ 4 = $2,965

You can also use a free online self-employment tax calculator (like the one at https://turbotax.intuit.com/tax-tools/calculators/self-employed/) to verify your math and get a quick estimate without doing all the calculations manually.

What is IRS Schedule SE and do I really need to understand it?

Schedule SE is the form that calculates your self-employment tax. Good news: if you’re using tax software, you’ll probably never see it. The software automatically fills it out based on your Schedule C income.

But it’s worth understanding the basics:

- It takes your net profit from Schedule C

- Applies the 92.35% multiplier

- Calculates 15.3% self-employment tax

- Shows you the deduction you get (50% of SE tax)

You DO need to file Schedule SE if:

- Your net self-employment earnings are $400 or more

- You’re reporting any self-employment income

You DON’T need to file it if:

- You only have W-2 income

- Your self-employment net earnings were under $400

Bottom line: Let your tax software handle it, but skim through the completed form before filing to make sure the numbers look right.

How can I avoid an IRS underpayment penalty as a freelancer?

The underpayment penalty happens when you don’t pay enough tax throughout the year via quarterly payments. Here’s how to avoid it:

Safe Harbor Method #1: Pay at least 100% of last year’s total tax (110% if your AGI was over $150,000). Even if you earn more this year, you’re protected.

Safe Harbor Method #2: Pay at least 90% of this year’s actual tax liability through quarterly payments.

Safe Harbor Method #3: Owe less than $1,000 in tax after subtracting withholdings and credits.

Practical tips:

- Make all four quarterly payments on time (April 15, June 16, Sept 15, Jan 15)

- Use the “previous year method” for automatic penalty protection

- If you miss a deadline, pay ASAP—don’t wait for the next quarter

- If income drops mid-year, you can reduce future payments

- Keep records showing how you calculated each payment

What if I still get penalized?

The penalty is usually modest (a few hundred dollars) and only applies to the quarters you underpaid. It’s not the end of the world, but it’s avoidable with planning.

What are the self-employment tax deduction rules for 2025?

The self-employment tax deduction has two parts:

1. The SE Tax Deduction Itself (50% of your SE tax)

- You can deduct half of your self-employment tax on Form 1040

- This is an “above-the-line” deduction (you don’t need to itemize)

- It reduces your Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)

- It lowers your income tax, but doesn’t reduce your SE tax itself

Example: You paid $8,000 in SE tax. You can deduct $4,000 from your taxable income, which saves you ~$880-$1,000 depending on your bracket.

2. Business Expense Deductions (These reduce your SE tax AND income tax)

- Home office deduction (if you have a dedicated space)

- Health insurance premiums (if self-employed and not eligible elsewhere)

- Retirement contributions (SEP IRA, Solo 401(k))

- Business expenses (software, equipment, mileage, professional development)

Key rules for 2025:

- Expenses must be “ordinary and necessary” for your business

- Keep receipts and documentation for everything

- Track mileage at 70 cents per mile (2025 standard rate)

- Home office must be used exclusively and regularly for business

- You can’t deduct personal expenses, commuting, or entertainment

The math:

More deductions → Lower net profit → Lower SE tax AND income tax → More money in your pocket

Is there a simple system for saving quarterly taxes from each payment?

Yes! Here’s the system that actually works (and the one I wish I’d used from day one):

The Automatic 30% Rule:

- Open a separate savings account called “Tax Savings”—completely separate from personal accounts

- Immediately transfer 25-30% of every payment you receive to this account

- Never touch that money except to make quarterly tax payments

- Pay yourself from what’s left after the transfer

Why 25-30%?

- 15.3% for self-employment tax

- 10-15% for federal income tax (varies by bracket)

- Add more if you live in a high-tax state

How to automate it:

- Use business banking apps like Novo, Relay, or QuickBooks that allow percentage-based auto-transfers

- Set the rule once: “When money arrives, move 30% to tax account”

- You never see that money as available to spend

The monthly reconciliation version:

If income is irregular, do this on the 1st of each month:

- Calculate last month’s total income

- Transfer 25-30% to tax savings

- Update a simple spreadsheet to track progress toward quarterly payments

The buffer system (advanced):

Once you’ve saved your estimated quarterly payment plus a 15% buffer, reduce your savings rate for the rest of that quarter.

Example:

Need $4,000 for April payment → Save until you hit $4,600 → Reduce savings to 20% for remaining March income → Reset on April 1st

Bottom line: Automation removes temptation. If you never see the tax money as “yours,” you won’t accidentally spend it.

What happens if I forget to make a quarterly tax payment?

Don’t panic—but do act quickly. Here’s what happens and what to do:

What happens:

- The IRS calculates an underpayment penalty for that specific quarter

- The penalty is based on how much you should have paid and for how long you didn’t pay it

- It’s essentially interest on the unpaid amount (current rate is around 8% annually, but it varies quarterly)

What to do:

- Pay immediately as soon as you realize you missed it—don’t wait for the next quarterly deadline

- Pay the full amount you should have paid for that quarter

- Continue with your regular schedule for future quarters

- Document your payment and keep confirmation

Can you avoid the penalty?

- If you paid at least 100% of last year’s tax (110% if high income), you’re protected even if you missed specific quarterly deadlines

- If you owe less than $1,000 total after withholdings, no penalty applies

- You can’t eliminate one quarter’s penalty by overpaying in a later quarter—each quarter is calculated separately

How much is the penalty?

Usually modest—often $50-$200 for a single missed quarter, depending on the amount. It’s not catastrophic, but it’s avoidable.

Pro tip: Set calendar reminders for all four quarterly dates at the beginning of the year. Better yet, if you use EFTPS (Electronic Federal Tax Payment System), you can schedule all four payments in advance.

How long should I keep my tax records and receipts?

The IRS recommends:

- 3 years for most records (from the date you filed, or 2 years from when you paid the tax—whichever is later)

- 7 years for records related to large purchases (equipment, vehicles) or if you claimed a loss from worthless securities

- Indefinitely for records related to property (real estate, business assets)

What to keep:

- All 1099 forms

- Receipts for business expenses (even small ones)

- Bank and credit card statements showing business transactions

- Mileage logs (date, destination, business purpose, miles)

- Invoices and contracts

- Proof of quarterly tax payments

- Prior year tax returns

How to organize:

- Use accounting software (QuickBooks, FreshBooks, Wave)

- Snap photos of receipts with apps like Expensify or Keeper Tax

- Create folders by year: “2025 Taxes” → subfolders for receipts, invoices, statements

- Back up digital records to cloud storage

Why it matters:

If the IRS audits you (rare, but possible), you need to prove every deduction you claimed. No receipt = no deduction. Keep everything organized and you’ll never worry

Final Thoughts: You’ve Got This (Really)

Look, I’m not going to sugarcoat it—your first year of self-employment taxes is going to feel overwhelming. You’re learning a new business, managing clients, and suddenly you’re also responsible for calculating and paying taxes like a business owner. It’s a lot.

But here’s what nobody tells you: by your second year, this becomes routine. You’ll know exactly how much to set aside, when payments are due, and which expenses to track. By your third year? You’ll barely think about it.

The key is getting the fundamentals right from the start:

✅ Set aside 25-30% of every payment automatically

✅ Make your four quarterly payments on time (April 15, June 16, Sept 15, Jan 15)

✅ Track every business expense, no matter how small

✅ Use the “previous year method” for safe harbor protection

✅ Keep your tax savings account completely untouchable

That’s it. Those five habits will save you from 90% of the stress, penalties, and panic that derail new freelancers.

And remember: the IRS actually wants you to succeed. They provide extensive resources, free calculators, and helpful publications. If you’re genuinely confused, call their helpline or work with a tax professional (which is itself a tax-deductible expense).

The higher taxes sting at first. I won’t lie about that. But you’re also earning more freedom, flexibility, and potential than you ever had as a W-2 employee. That trade-off? It’s worth it.

You’ve got this.

⚠️ DISCLAIMER: This article is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be considered professional tax, legal, or financial advice. Tax laws are complex and change frequently. Individual circumstances vary significantly, and what applies to one person may not apply to another. While this guide is based on 2025 IRS guidelines and current tax regulations, you should always consult with a qualified CPA, Enrolled Agent, or licensed tax professional before making any tax-related decisions. The author and publisher are not responsible for any actions taken based on the information provided in this article. Always verify current tax rates, deadlines, and regulations with official IRS resources or your tax advisor.